Erymanthos is a magical place. It feels rustic and remote, and quite different from the two other big mountain ranges that dominate the northern Peloponnese, Kyllini and Chelmos, where you are never too far away from the ski lifts.

This route takes you on a beautiful path up to the highest peak, Olenos (2244 metres). I was there in early June 2025. I don’t think I have ever heard so many bees in one place: the air is thick with them as you wade through the sea of waist-high yellow flowers that cover the mountainside.

Erymanthos in myth

Erymanthos doesn’t have a prominent archaeological heritage. There’s no evidence for a summit altar. That’s quite typical for the higher mountains: it’s often slightly lower peaks closer to settlements that became places of worship in antiquity.

It’s referred to frequently but often quite briefly in ancient mythological texts.

For example, there is the story of Callisto, who is seduced by Jupiter on Mount Mainalos, turned into a bear by Hera, and then nearly shot by her son Arkas on the slopes of Erymanthos: Zeus whisks them up into the heavens just in time, to stand as the constellations of the Great and Little Bear.

The killing of the Erymanthian boar by Herakles is often referred to in just a few words, in accounts of his twelve labours.

In Odyssey Book 6, just before Nausikaa meets the shipwrecked Odysseus, she is said to stand apart from the other girls who accompany her:

just as Artemis, the shooter of-arrows, goes over the mountains, either very high Taygetos, or Erymanthos, taking pleasure from the boars and swift deer, and together with her the wood-dwelling nymphs, daughters of aegis-bearing Zeus, share in her play. (Homer, Odyssey 6.102-5)

That’s typical of the way in which ancient poets so often conjure up images of mountains as enchanted places, landscapes that the gods move through effortlessly and joyfully.

Oddly the thing that interested the ancient commentators most of all about these lines was the poet’s failure to mention lions, which are a standard feature of many other mountain descriptions in Homer. They took this as a reflection of the absence of lions in the Peloponnese.

Erymanthos in erotic epigram

But my favourite Erymanthos text is an epigram. We have thousands of epigram poems surviving from antiquity. They are some of the most underrated of all ancient texts. They tend to be very short, just a few lines long, often in the first person, many of them on erotic subjects. They often adapt images from earlier literature and play on their reader’s expectations in fantastically ingenious ways.

In this case we have a speaker who wants to give expression to the enormity and unlikeliness of the change he has undergone in his love life:

I am no longer mad for boys, as I was before; now I am now called mad for women; now my discus has become a rattle. Instead of the unadulterated complexion of boys, I now take pleasure from skin covered in chalk, and from the adorning blossom of rouge. Tree-crowned Erymanthos will be a feeding place for dolphins, and the wave of the grey sea for swift deer! (Greek Anthology 5.19)

Part of the power of the poem comes from its sense of paradox—not just the spectacular image of dolphins in the forests of Erymanthos, but also the incongruity between the claustrophic, deeply intimate, urban character of the gossipy first half of the poem, and the wilderness of Erymanthos in the second half.

Dolphins

But why dolphins?

There’s one parallel from Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book 1, where he is describing the great flood, which turns land into sea:

Dolphins occupy the woods, dashing against the high branches, and shaking and knocking against the oak-trees. (Metamorphoses 1.302-3)

Here the idea of dolphins swimming through forests is powerfully linked with a paradoxical inversion of day-to-day reality, and the epigrammatist may well have this passage in mind.

But is there any more specific association with Erymanthos?

If so, it is most likely to be via a link with Herakles. For reasons that are not clear to me Herakles often depicted in Greek vase paintings and coins with dolphins in the background.

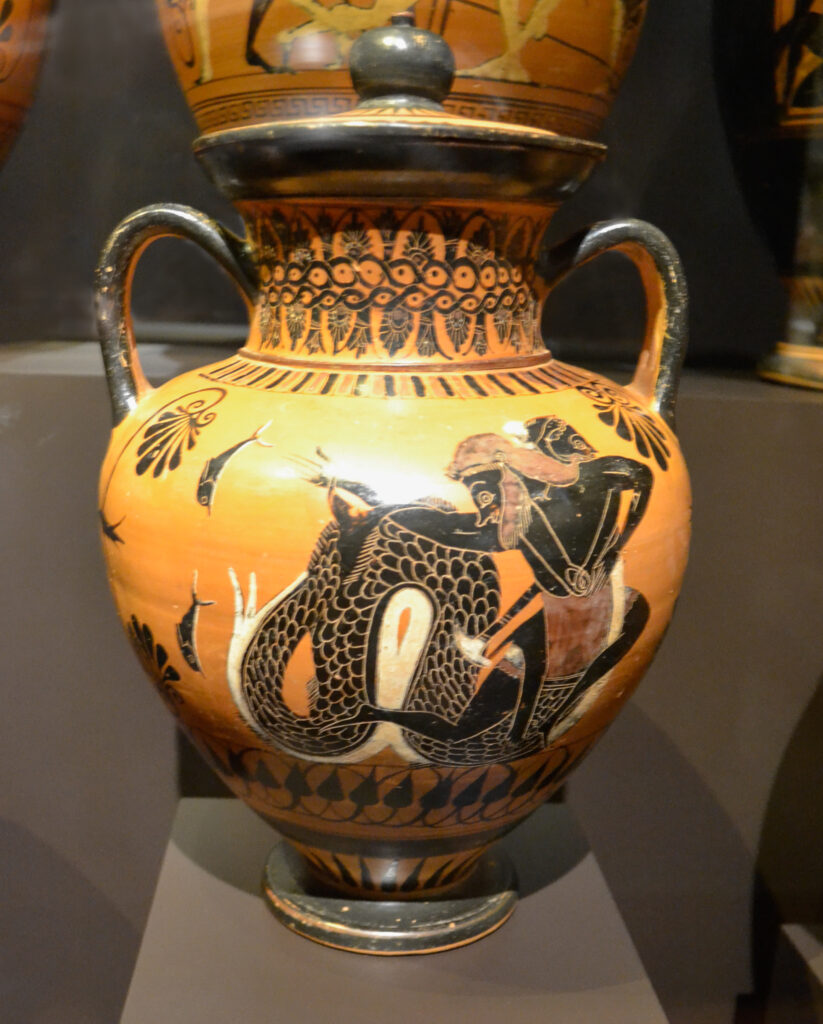

Here he is in two different vase images, wrestling with Triton, son of the sea god Poseidon:

Towry Whyte Painter – ABV 142 6 – Herakles and Triton – Herakles and the lion – Würzburg MvWM L 263

Herakles and Triton, Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España

One of his other famous deeds was his rescue of the princess Hesione from a sea-monster, also sometimes portrayed with dolphins in the background.

Intriguingly the goddess Athene also appears in one image with a dolphin on her shield, instead of the usual owl, watching Herakles deliver the Erymanthian boar to king Eurystheus (who is so frightened that he hides in a jar).

Erymanthos had always been associated with animals—we can see that from the Odyssey passage too: the deer, the boar, the mysteriously absent lions. The dolphins are one more to add to the list.

Can you imagine them there, moving between the trees, swimming through the thick flowers and the waves of bees, as you hike your way up to the summit?

The route

From the village of Michas, the Olenos summit looks quite inaccessible, blocked by a long and thickly wooded ridge line of lower peaks. This path bypasses those difficulties magically, skirting the slopes of the ridge, ascending gently, with frequent glimpses of Olenos peeping over the other summits.

There’s some optionality on the first part of the ascent. From the centre of Michas (plenty of space to park) you follow the road to the west, then very soon take a left fork. From there you can either fork left again on a path that leads up into the forest (with a signpost to the various Erymanthos peaks) or else keep straight on and follow the winding forest road past beehives and steadily upwards.

The two routes join up with each other less than 2 km later, at the crucial turn-off. At that point the forest road bends round to the right, heading south west. The path to the summit goes straight ahead up the slope into the trees.

It’s well signposted, with red paint splashes all the way up. It comes out into a small meadow, with views of the ridgeline ahead.

There were goats and a couple of small dogs there (barking a lot, but nothing worse!) when we passed through.

From there you follow the path south west as it winds its way around the folds of the mountainside. You go past a shepherd’s hut (deserted when we went past). At one point there is a landslip, which you can cross with care—or else you can avoid it by clambering up and following the bypass path higher up the slope.

The path is gentle all the way until you get to the final steep push up to the summit.

From Michas to the Olenos summit and back is 16 km and 1300 metres of ascent.

If you want a shorter day out you could go as far as the landslip and back again: that is 10 km, and 750 metres of ascent.

For detailed mapping, see the Anavasi Topo25 map 8.61 (‘Mt Erimanthos’).

For other good accounts of hiking on Erymanthos, see here and here.

The start point for the route is here. The downloadable GPX file is below.